The History of Sciacca

Sciacca was originally located within the territory of Selinunte, which included the famous thermal baths—known in ancient times as the Thermae Selinuntiae or Aquae Selinuntiae—about twenty miles east of Selinunte.

Although the exact date of Sciacca’s foundation is uncertain, the most likely theory is that it was founded—or rather repopulated—by the inhabitants of Selinunte after their city was destroyed by the Carthaginians in 409 BC. According to the historian Diodorus (90–27 BC), many survivors fled to Agrigento, but when the Carthaginian storm had passed, they returned to rebuild or settle nearby, giving birth to a new village: Sciacca.

Historical sources confirm the city’s ancient origins. The Roman geographer Pomponius Mela (1st century AD) wrote that “inter Pachynum et Lilybaeum Agragas est et Heraclea et Thermae”—meaning “between Pachynus and Lilybaeum there were three cities: Agrigentum, Heraclea, and Thermae (Sciacca).” Likewise, Strabo (58–25 BC) referred to “Termà Selinoùntia”, or “the Baths of Selinunte.”

After Selinunte’s destruction, many people took refuge in Thermae, which grew in population. Being a border city, it was long contested by the Greeks, Carthaginians, and eventually the Romans, who conquered it after the First Punic War. Under Roman rule, Sciacca became an important city and remained so for centuries, serving as one of the main postal hubs of Sicily.

The fall of the Roman Empire marked the end of Sciacca’s prosperity, as the city suffered destructive invasions by the Vandals and the Goths. When the Byzantines, under Emperor Justinian, regained control of Sicily, hermit monks began to settle in the Sciacca area. Among them was Saint Calogero, who spread Christianity across several parts of Sicily and lived as a hermit in a cave on Mount Kronio, now known as Mount San Calogero.

However, it was the Arabs who left a lasting mark on Sciacca—on both its history and its name. From the 9th century onward, during their Mediterranean expansion, they conquered Mazara in 827 and, by 840, took control of the thermal area, naming it As-Saqqa, which eventually became Sciacca. The Arabs fortified the city with massive walls and a tower, later strengthened under the Normans and Frederick II (1194–1250).

Count Roger (1031–1101) built the famous Old Castle. Sciacca remained under Norman rule and their descendants for many years, notably governed by the descendants of Giliberto Perollo, a Burgundian nobleman who had come to Sicily with Count Roger.

From 1208, Sciacca and Sicily were ruled by Frederick II and his heirs until the rise of Charles of Anjou (1226–1285). Sciacca took part in the Sicilian Vespers War against Angevin rule and was later governed by Guglielmo Peralta, who commissioned the construction of the New Castle.

Throughout the 16th century, Sciacca became the stage of fierce rivalries among the Peralta, Perollo, and Luna families. Between the 17th and 19th centuries, the city came under Spanish and later Bourbon rule, until the unification of Italy in 1861.

Luna Castle

Luna Castle

The Luna Castle is located in the northeastern upper part of Sciacca, on the outer edge of the city’s ancient defensive walls. From this position, it still dominates the deep valley that opens beyond the ring road skirting the walls, offering a view that stretches all the way to the coast.

The castle was built in 1380 by Guglielmo Peralta. It later passed into the hands of the Luna family when Margherita, one of the three daughters of Nicolò Peralta (Guglielmo’s son), married Count Artale of Luna.

The castle stands on massive rocks, in a commanding position on the easternmost side of the city, and forms part of the old perimeter walls—some of which still survive today. It consists of four main structures: the walls, the tower, the Count’s palace, and a cylindrical tower.

The defensive walls were polygonal in shape, high and solid. Inside the perimeter stood the main square tower, which rose well above the rest of the complex and served as a watchtower over the walls, the surroundings, and the inner courtyard. It remained intact until 1740, when a violent earthquake severely damaged it, leaving only the base still visible today.

The cylindrical tower, located on the southern side of the walls, still stands and has two levels. The Count’s Palace, rectangular in shape, was located on the western side of the castle between the main tower and the cylindrical one. It had a ground floor used for service quarters and an upper floor where the Count and his family lived. Today, only the tall outer wall with four large windows remains.

The entrance was on the northern side and originally featured a drawbridge, leading into a courtyard that contained the stables, soldiers’ quarters, and a chapel dedicated to Saint Gregory. A staircase on the right side led to the noble floor.

Although not monumental in size, Luna Castle remains one of the most fascinating examples of 14th-century civil and military architecture in Sicily. Its commanding position overlooking Sciacca gives it a distinctive and evocative presence that enhances the city’s skyline with beauty and character.

The castle is also tied to the legend of the “Case of Sciacca”, a bloody feud between two noble families—the Luna family of Catalan origin and the Perollo family of Norman descent—that tormented the city for nearly two centuries.

The Gates of Sciacca

The Gates of Sciacca

In ancient times, Sciacca was surrounded by defensive walls built to protect the city from external attacks. To enter and leave the town, people used several city gates known as Porta Palermo, Porta San Salvatore, Porta di Mare, Porta Bagni, and Porta San Calogero.

Porta Palermo was built in 1753, during the reign of Charles II of Bourbon, and still preserves its original wooden doors along with the royal family’s emblem — an eagle with outstretched wings.

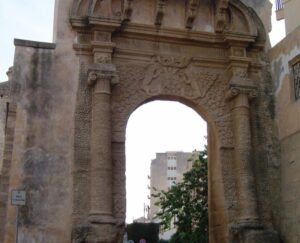

The Porta San Salvatore is the oldest and most ornate of Sciacca’s gates, leading directly into the historic center. It is also considered the most beautiful, with its pure Renaissance style, featuring two elegant columns and a rounded arch.

At the base of the columns stand two carved elephants, seemingly supporting the entire structure. The façade is richly decorated with arabesques, rosettes, lion heads, and bas-reliefs depicting two lions.

At the top, there are three coats of arms representing the ancient symbol of the city, the House of Austria, and the Sotomajor family, who commissioned the construction of the gate.

Of all the ancient gates, Porta Palermo, Porta San Salvatore, and Porta San Calogero are the only ones that still remain today, serving as timeless reminders of Sciacca’s rich architectural and cultural heritage.

The Enchanted Castle

The Enchanted Castle

Nestled beneath Mount Kronio, just a few kilometers from the town of Sciacca, lies the Enchanted Castle (Castello Incantato) — a fascinating open-air museum filled with mystery, art, and charm.

This extraordinary place was shaped by both human imagination and nature. Among olive and almond trees rise thousands of sculpted heads, carved into rock, tree trunks, and branches by the local self-taught artist Filippo Bentivegna, affectionately known as “Filippu li testi” (“Philip of the Heads”).

His creations are diverse, depicting both famous and unknown figures. Bentivegna gave them invented names, symbolizing the inhabitants of his imaginary kingdom, where he saw himself as the King. Locals called him “Your Excellency,” a title he embraced with pride.

After his death, the property — along with over 20,000 sculptures — was abandoned for years. Many works were partially destroyed or lost. At the center of the estate stands Bentivegna’s small home, its interior walls decorated with paintings of skyscrapers and fish, offering a glimpse into his surreal and poetic world.

Today, the Enchanted Castle of Sciacca remains a must-see attraction for visitors seeking something truly unique — a place where art, nature, and eccentric genius intertwine.

Some of Filippo Bentivegna’s sculptures are now exhibited at the Musée de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, dedicated to the memory of artist Jean Dubuffet, who celebrated outsider art around the world.

The Thermal Caves of San Calogero

The Thermal Caves of San Calogero

Mount San Calogero,

standing 395 meters above sea level, lies at 10°45′ east longitude and 37°24′ north latitude. Geologically, its formation dates back to a transitional period, closer to that of ancient volcanic activity. The mountain is composed mainly of ferruginous limestone, rich in calcite, silica, alumina, magnesia, and abundant iron oxide.

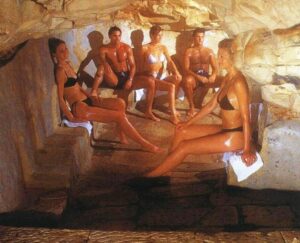

Among the many natural caves found on the mountain, the most fascinating is undoubtedly the “Stufa di San Calogero” (literally “the Stove of Saint Calogero”). Inside this remarkable grotto, the temperature ranges from 36°C to 42°C, depending on the season and time of day.

The walls show chisel marks and ancient inscriptions, now barely legible, suggesting Greek or Saracen origins. Inside, one can still see stone benches and niches where the sick once sat, as well as small hollows used to place limbs—arms or legs—so the thermal vapors could reach specific areas of the body for healing purposes.

In 1880, the Municipal Council of Sciacca commissioned Professor Silvestro Zinno to conduct a detailed analysis of the cave’s waters and vapors, with the goal of verifying their chemical composition and therapeutic properties. Based on his research, Professor Zinno concluded that the vapors of San Calogero’s grotto were effective in treating arthritis, rheumatism, and related ailments. The thermal waters were also found to benefit those suffering from neuralgia, sciatica, and certain skin conditions accompanied by severe itching.

The recommended duration of a session in the Stufa ranges from ten to twenty minutes, depending on individual tolerance. According to historical accounts, the Stufe di San Calogero can produce remarkable effects, such as cleansing the body of impurities and stimulating the nervous system. The pure mountain air is also said to enhance the healing process.

The San Calogero Sanctuary, located on the same mountain, was built in 1530. Since 1948, it has been under the care of the Third Order Regular of Saint Francis of Penance. In 1979, Pope John Paul II elevated it to the status of a minor basilica. Inside, it houses a magnificent statue of Saint Calogero sculpted by the renowned artist Antonello Gagini.

The Coral of Sciacca

The Coral of Sciacca

The Coral of Sciacca has its origins in an extraordinary historical event: the sudden emergence of a volcanic island from the depths of the Mediterranean Sea — later known as Ferdinandea Island. Today, the island lies submerged between Sciacca and Pantelleria, but its legacy lives on beneath the waves.

According to legend, this underwater treasure, unique in the world, was discovered in 1875 near Ferdinandea Island by a local fishing captain nicknamed “Bettu Ammareddu.” While fishing with his companions, Bertu “Occhi di Lampa” and Peppe Muschidda, Bettu accidentally lost a necklace — a love token and good-luck charm gifted to him by his beloved Tina. Diving into the sea to retrieve it, he instead discovered vast fields of coral lying on the seabed.

The discovery was later immortalized in the poem “La Corallina” by Vincenzo Licata, a poet from Sciacca.

The Sciacca coral, a rare variety of Corallium rubrum, grows in slender, elongated branches and usually measures no more than 8–9 millimeters in diameter. The main coral bank, known as the Graham Bank, is located about 30 miles off the coast of Sciacca.

What makes this coral truly exceptional is its unique coloration, ranging from delicate pale pink to deep salmon, often marked with shades of yellow, brown, or even black.

As a natural product of the sea, each branch of Sciacca coral is a one-of-a-kind masterpiece, impossible to replicate. Local artisans such as Nocito, Sabrina Orafa, and L’Oro di Sciacca celebrate this uniqueness through exclusive handcrafted jewelry, each piece capturing the soul and beauty of the Mediterranean.

The Carnival of Sciacca

The Carnival of Sciacca

The Carnival of Sciacca, is the oldest in Sicily and one of the most famous in Italy, thanks to a century-old tradition that continues to captivate visitors every year. Towering papier-mâché floats up to 12 meters high, vibrant costumes, and original music are all handcrafted by the talented artists of Sciacca.

The Carnival Museum of Sciacca is a magical treasure chest preserving over 100 years of history of this extraordinary celebration — a journey through time that tells the story of a festival born from the joy and creativity of an entire community.

Inaugurated in 2010, the museum sits in a garden overlooking the sea and houses a rich collection of exhibits that celebrate the art and spirit of the Sciacca Carnival. Among the most remarkable are around 100 miniature papier-mâché floats, faithful reproductions of the grand allegorical floats that have paraded through the streets in past editions. Each piece is a true work of art, handcrafted and painted in ceramic by Sciacca’s master artisans.

Even before entering, visitors are immersed in the colorful world of the Carnival. The museum’s entrance hall recreates some of Sciacca’s most beautiful historic palaces, reconstructed from fragments of past floats that once lit up the streets with color and movement.

Inside, the first gallery presents a photo exhibition, including 3D images, capturing the most striking and emotional moments of the Carnival’s long history.

The next section displays historic costumes, each closely tied to the allegorical theme of its original float — a testament to the attention to detail and artistry that have always characterized Sciacca’s masquerade tradition.

The final area features the miniature floats, all handcrafted in traditional Sciacca ceramics, representing decades of craftsmanship, creativity, and community pride.

The Sciacca Carnival remains not only a festival but a living expression of Sicilian joy, imagination, and cultural heritage — a spectacle that enchants both adults and children alike.

The Port of Sciacca

The Port of Sciacca

The Port of Sciacca is primarily a fishing and commercial harbor, home to around 500 boats, including fishing vessels and small crafts. Every year, these boats bring in more than 4,000 tons of bluefish, freshly caught from the rich waters of the Mediterranean.

The main fishing methods practiced in this area are trawling, inshore fishing, and longline fishing. The most common catch belongs to the bluefish family, particularly the purse seine fish, which is processed on land by the numerous seafood preservation industries. Thanks to this thriving trade, Sciacca is recognized as one of Europe’s leading producers of preserved bluefish.

When the fishing boats return to port, it becomes a vibrant festival of the senses. The docks fill with tons of fresh fish and seafood, transforming the pier into a lively open-air market.

It’s a colorful southern spectacle: fishermen turn into theatrical merchants, displaying their glistening treasures in shades of red, gold, and silver. The turquoise sea and the ancient town of Sciacca create a stunning backdrop, while the air carries the unmistakable scent of the South — salt, sun, and sea breeze blending into a perfect Mediterranean harmony.

The Ceramics of Sciacca

The Ceramics of Sciacca

Sciacca is not only known for its sea, thermal baths, and cultural heritage — it is also a land of artisanal mastery.

Walking through the historic center of Sciacca, it’s impossible not to notice the many shops displaying vibrant, colorful ceramics in every shape and size.

Sciacca’s ceramics are a major attraction for visitors who wish to take home a piece of the town’s rich artistic tradition — a craft with ancient origins and a deep connection to local identity.

The artisanal tradition of Sciacca finds its purest expression in majolica pottery, and it is said that as early as 1282, the town’s kilns were already producing glazed ceramic ware.

In fact, the origins of Sciacca’s ceramics date back to the 8th–6th millennium BC, and the craft still preserves the forms and colors of ancient tradition, thanks to the Giuseppe Bonachia Art School, named after the great local master potter and majolica artist.

Today, Sciacca is home to around fifty artisan workshops, offering a wide variety of hand-decorated majolica items: tableware, decorative ceramics, figurines, votive tiles, plates, vases, and jars. These are painted in the traditional colors loved by Sciacca’s artisans — blue, copper green, straw yellow, orange, and turquoise.

In recent years, thanks to local and regional initiatives, the Association of Sciacca Ceramists has successfully revived public interest in this unique art form. Their work has earned national recognition for the quality of Sciacca’s majolica and created new opportunities for export across Italy and beyond.

The ceramics of Sciacca remain a living symbol of Sicilian artistry, combining history, color, and creativity into timeless handmade beauty.

The Basilica of Our Lady of Relief – Patron Saint of Sciacca

The Basilica of Our Lady of Relief – Patron Saint of Sciacca

In 1108, Giulietta the Norman, daughter of Count Roger I of Sicily, ordered the construction of the Basilica of Our Lady of Relief (Madonna del Soccorso) in the heart of the ancient Ruccera quarter.

Known as the Lady of Sciacca from 1100 to 1136, Giulietta’s life intertwined romance and faith — particularly her troubled relationship with Roberto I of Bassavilla, opposed by her father. As an act of repentance and devotion, she dedicated to the Virgin Mary the largest and most magnificent church ever built under the rule of the House of Altavilla in Sciacca.

Another version attributes the construction to Father Roger d’Altavilla, who built it as a votive offering of gratitude to the Virgin Mary under the title of the Assumption. The Altavilla family often erected churches and cathedrals on the sites of their most fierce battles against the Arab invaders, as part of the long process of re-Christianizing Sicily.

A key moment in the basilica’s history occurred on February 1, 1626, when the people of Sciacca began a solemn pilgrimage known as “U Vutu”, walking from the Church of St. Augustine to the Mother Church, to seek deliverance from a devastating plague.

The next day, the statue of the Madonna joined the procession, carried by a large group of fishermen. As they reached the area known as Piccola Maestranza, a sudden lightning bolt struck from a clear sky, hitting the feet of the Virgin’s statue. A cloud of smoke spread through the city — and at that very moment, the miracle of Sciacca’s liberation from the plague occurred.

From that day on, Our Lady of Relief became the patron saint of Sciacca. Twice a year, on February 2 and August 15, the sacred statue is carried in a grand procession by barefoot fishermen, who bear the heavy 17th-century wooden float adorned with gold, silver, and coral jewelry — offerings from grateful devotees.

The Basilica of the Madonna del Soccorso remains one of the most important symbols of faith, tradition, and identity for the people of Sciacca.

The Beaches of Sciacca

The Beaches of Sciacca

The variety of Sciacca’s coastline offers something for every traveler. From sandy shores to rocky coves, the sea and landscape meet every taste and desire of those visiting our city.

Just a short walk from the city center, the first beach you’ll find is Lo Stazzone, followed by Lido, La Tonnara, and Foggia — all known for their wide stretches of golden sand.

Further along, the beaches of San Marco, Renella, and Maragani feature both sandy and rocky areas, creating true paradises for swimmers and scuba divers.

East of the city, along the old road to Ribera, you’ll come across Sovareto Beach, famous for its fine sand. Continuing along the same road, you’ll find Timpi Russi and San Giorgio, two beautiful beaches nestled among small and wide inlets, all with soft, golden sand.

In almost all these areas, you’ll find beach clubs, restaurants, and seaside kiosks where you can relax and enjoy local specialties by the sea.

Ferdinandea Island

Ferdinandea Island

Sicily has long been known by Mediterranean peoples as the “Land of Fire.” Among its famous volcanoes — including Mount Etna, the islands of Stromboli, and Vulcano — lies Ferdinandea Island, the newest and most restless of them all.

On June 28, 1831, violent earthquakes shook the coast of Sciacca, causing significant damage and generating impressive waves that were felt as far as Palermo. These tremors continued until July 10. During those days, extraordinary phenomena occurred in Sciacca: returning fishermen reported areas where the sea boiled violently and dead fish floated on the surface; silver objects blackened due to a strong smell of sulfur; and from the town’s central square, a clear column of smoke was seen rising from the sea.

On July 17, amid thunderous sounds and sulfurous fumes, a new island emerged from the sea, crowned by a column of black smoke. Its rapid growth in size and height was fueled by pumice, lava, and lapilli erupting violently from the two craters that surfaced from the ocean depths. The island appeared on what Sicilians called the “secca di mare” and the Maltese referred to as “Graham Bank,” about 30 miles south of Sciacca.

Sciacca sent the first exploratory delegation, led by Commander Michele Fiorini, who planted an oar on the island as a sign of discovery. By August 1831, the previously violent eruptions ceased. The island measured about 4,800 meters in circumference, rising steeply from a depth of 200 meters to a maximum height of 70 meters above sea level, with two acidic saltwater lakes at the craters’ centers. The island became a subject of study for prominent French, English, and Italian scientists, including Professor Gemellaro.

On August 2, Captain Sanhouse raised the British flag at the island’s highest point, naming it “Graham Island.” Later, on August 17, Ferdinand II of Bourbon, King of the Two Sicilies, annexed it to his kingdom with the royal decree naming it “Ferdinandea Island” in his honor. For the local people, it remained simply “the Island of Sciacca,” valued mainly for its strategic position.

Today, Ferdinandea lies 8 meters below sea level, yet it still holds a special place in people’s hearts, commemorated by a plaque placed by divers at its summit.

Luna Castle

Luna Castle The Gates of Sciacca

The Gates of Sciacca The Enchanted Castle

The Enchanted Castle The Thermal Caves of San Calogero

The Thermal Caves of San Calogero The Coral of Sciacca

The Coral of Sciacca The Carnival of Sciacca

The Carnival of Sciacca  The Port of Sciacca

The Port of Sciacca The Ceramics of Sciacca

The Ceramics of Sciacca The Basilica of Our Lady of Relief – Patron Saint of Sciacca

The Basilica of Our Lady of Relief – Patron Saint of Sciacca The Beaches of Sciacca

The Beaches of Sciacca Ferdinandea Island

Ferdinandea Island